Client

Building Contractors Consortium Katwijk (ACK) / Rabo Vastgoed, Utrecht

Period of design through completion of construction: 1995 – 2005

Chronology

Floor Space

400 apartments, 5.000 m2 of retail and commercial space, two parking garages (600 spaces)

Urban Design Supervisor

Hans van Olphen Architects Partners, Amsterdam

Awards

Nomination Incentive Intensive Land Use STIR

Four parties working together in the project

The investor: RABO Vastgoed (owned by RABO Bank Utrecht)

Contractors Consortium Katwijk” (ACK)

Five architects and Hans van Olphen as supervisor

Bouwstart: provided the final drawings, thus forming the link between the designers and the contractors

Five Collaborating Architecture Offices

Jan Poolen (www.zeep.eu)

Theo Verburg (www.theoverburg.nl)

Cees Brandjes (www.brandjesvanbaalen.nl)

Bert Tjhie (www.tekton-architecten.nl)

Gerben van Manen (www.van-manen.com)

Background

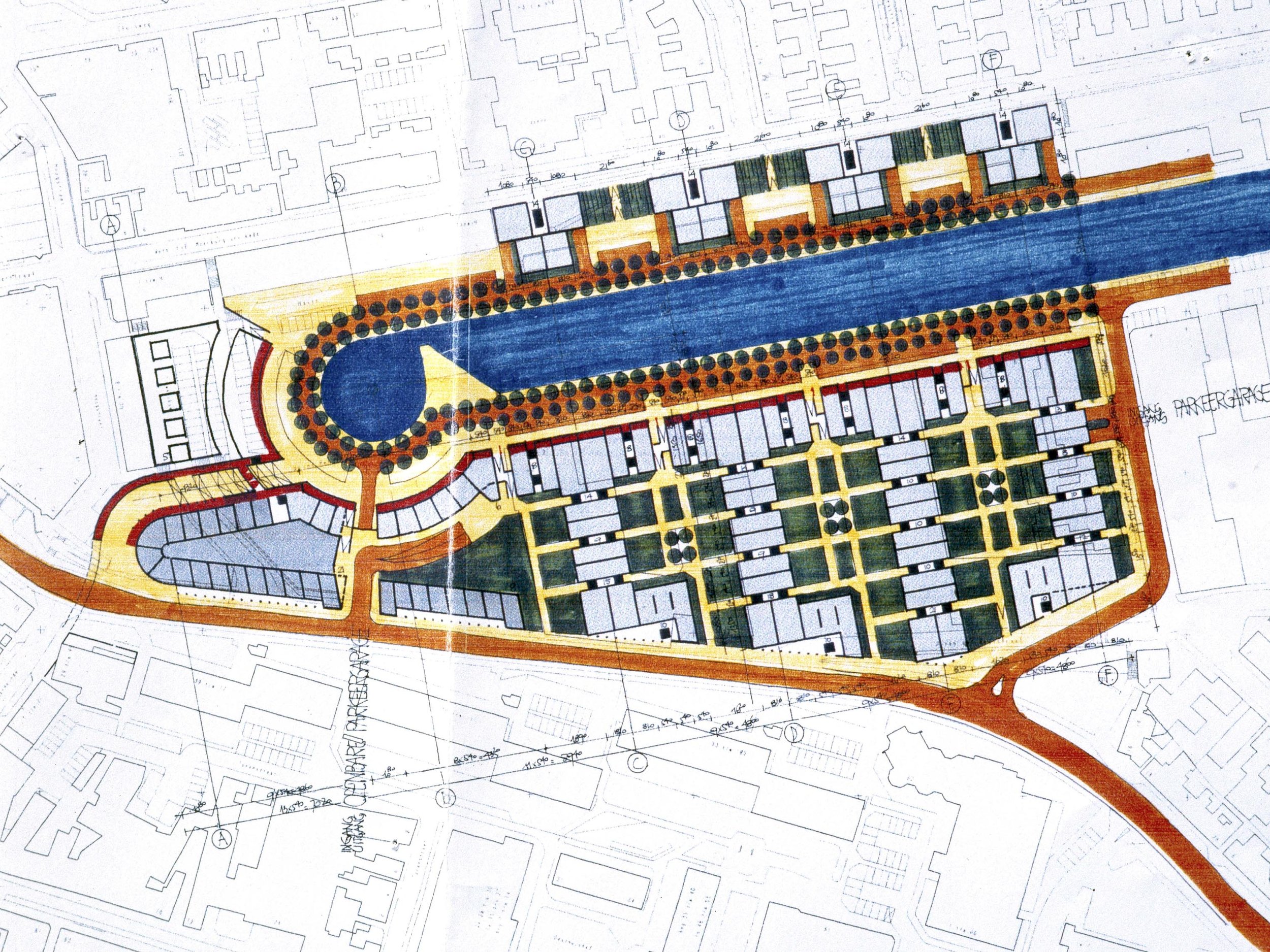

In the old harbor of Katwijk, local fishing company facilities have made room for 400 new apartment units and shops. The requirements of the development, dubbed Princehaven, stated that it needed to become a place that Katwijk citizens could identify with. The residents of Katwijk did not want to experience any separation between themselves and adjacent the village of Port Prince. This has been considered in the design and architecture of the development. The investor, RABO Vastgoed, worked closely with local developers and the municipality to negotiate a land development scheme that was amenable to all parties. The apartment blocks are focused around the harbor and provide residents of the upper floors views of the town of Katwijk. Large arcades provide residents with a desirable level of protection from inclement weather, while maintaining a sense of community. The new neighborhood functions as a 6m (20 ft.) high ‘bowl’ that frames the town, whereas portions of the development experience direct access from the street level with the older fishing cottages. The architecture of the apartments is sensitive to the vernacular style and scale of the existing fishing cottages. Throughout Princehaven, physical connections have been established in the form of stairways, lifts and roads, providing residents with easy accessibility to the town. The inner courtyards of the development include playgrounds, green space, ventilation and circulation, thereby giving a sense of intimacy between the blocks. The new development has become a critical component of the success of the town.

Note from Hans Van Olphen, supervising architect

“I was one of three architects invited to propose a scheme for the renovation of the inner harbor area of the town of Katwijk in the Netherlands, an area close to the town center. The municipality of Katwijk was the initiator, working in close cooperation with three local building companies (ACK) and a national bank as investor. They asked for an integrated plan for a large number of residential units combined with facilities like retail space and other commercial space and sufficient parking.

My plan was unanimously preferred after one meeting because it combined two important aspects.

1) The proposal offered a vision of the expected kind of environment without defining the exact final result. It allowed various ways of execution by other architects. This satisfied an important request from the municipality.

2) The proposal defined the envelope for built volumes while differentiating capacity for residential units, parking and commercial functions. This made calculation of the costs for execution possible before the actual partial designs were done.

3) The harbor area is situated at a lower elevation than the surrounding streets of the town. Because of the limited daylight, the lower levels behind the arcade contain the parking facilities (underground) as well as shops serving the whole neighborhood, opening onto the arcade.

My task was to design an Urban Plan in the sense of a Master Plan. Five architects participated in the project and accepted the rules of the Master Plan. My task was to protect the total as a whole. That was the reason I designed the 200-meter-long arcade to bring unity to the project despite the differences in architecture. Architects are generally individualistic, but in this project, they had to follow my organizing concept. The variation the architects realized was not in the ultimate facade or structure but in the living possibilities: for example, in the design of floor plans.

I was asked to work out the Master Plan within which were defined building heights, the parking garage and other infrastructural elements like stairways and elevators that, in turn, could be translated into rules and constraints within which architects had to work. After approval of the Master Plan, I was given the task of supervision of the designs done by the yet to be invited architects.

Together with the municipality and its partners I organized an excursion to several coastal towns in the north of France, to show that a general building height of seven floors need not result in the massive uniformity that the municipal representatives worried about as long as the buildings were designed by a variety of architects working on a variety of locations while sharing architectural themes. In Le Havre, Honfleur, Rouen, and other towns, we could see how narrow parcels make height of buildings a relative concept. This after all is also typical for the buildings along the Amsterdam canals. The excursion also helped to strengthen social contacts which made for a stimulating experience in spite of the different interests of the participants.

The architects to design the buildings were selected by the various client development parties. I could help steer it as well. The invited architects had to accept the detailed constraints of the Master Plan. The actual process towards the final design approval included workshops chaired by me. I completed the preliminary design for the arcade before the workshop with the architects had begun. The design of the arcade did not change after discussions and my explanations.

At that time, this offered an entirely new concept for the participating architects. The designs were discussed every two weeks with all architects present, a process which stimulated all participants. Architects could do proposals for the facades of their buildings, etc. But staircases, lifts, and other more structural elements were collectively decided. The beginning was somewhat difficult; the limitations set by the Master Plan and its rules were seen as a handicap. Gradually this was forgotten, particularly when it appeared that good architecture usually had its own rules and limitations that were often self-imposed. The architects found their way to design their own facades, window frames, balconies, etc., something that I stimulated (see Figures 1-5). Variation should be possible within my masterplan, otherwise my plan was not good. Eventually everybody subscribed to the final result.

One office (Bouwstart) was selected to make the entire set of building construction drawings after the definite design was finished by all the architects. Bouwstart finalized the project for the contractors, controlled the costs and managed the project execution. Parts of the arcade were built together with the adjacent residential buildings. The Contractors’ Combination Katwijk appointed one of its members as the responsible contractor to build the whole project, including the parts on the opposite sides of the harbor.

The contracts with the architects include all ownership rights and are comparable to other normal jobs. Professional fees are paid by RABO bank. Bouwstart and the architects worked together as is usual in our profession without any exceptional guidance.

“Using the Open Building principle of separation of design tasks and the ensuing workshops were a great experience in the Katwijk project. This way of cooperation points individual efforts to the quality of the whole and away from the individual identification of each architect. The project as a whole is central. It seems to me a real achievement that a residential project combined with shops, offices and hidden parking has become an environment of which no one knows exactly anymore who did what exactly.”

The supervising architect predetermined the location of elevator shafts that allow residents to reach their dwelling units directly from the underground garage. This makes these shafts part of the higher-level framework and an extension of public circulation around which the actual buildings, designed by different architects working for different developers, were designed. Apartment buildings behind the continuous urban wall interact intimately with this public circulation.

More than 25 years after the project was realized, the area remains very popular thanks to the collective efforts of all participants.