Project Data

HED (Architect of Record and Collaborating Design Architects); Moore, Rubel, Yudell Architects and Planners (Consulting Design Architects)

Architects

Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District, Santa Monica, California

Client

McCarthy Building Companies, Inc.

General Contractor

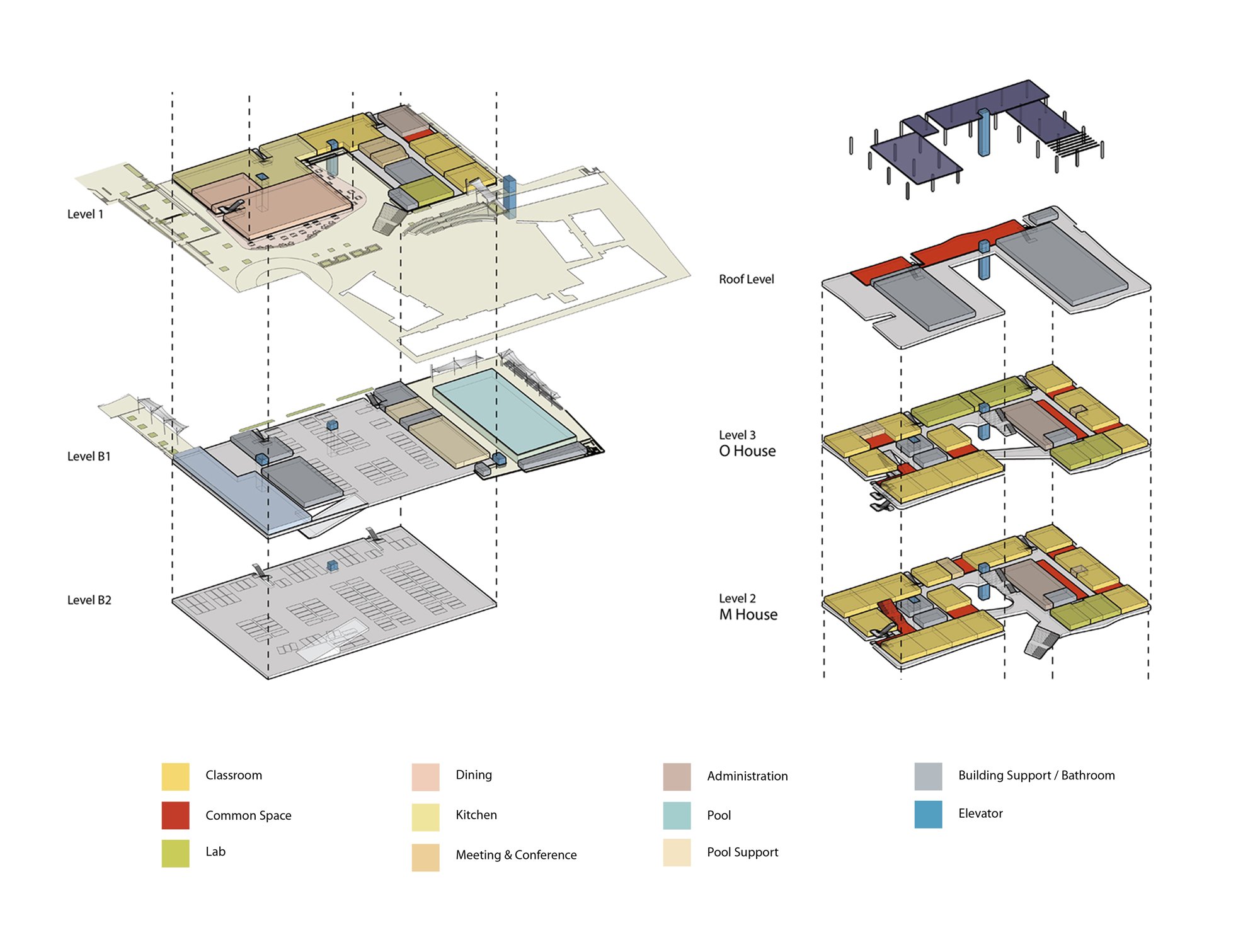

260,000 ft2 (24,155 m2)

Building Area

Prefabricated steel moment frame with a uniform structural grid. Typical bay size is 32’x38’ (2.97m x 3.53m). The structural grid extends into the two basement parking levels where the structural system is concrete columns and flat slabs. The lateral seismic system relies on the steel moment frame with some concrete shear walls at the basement levels.

Three stair cores are positioned around the building’s perimeter to maximize uninterrupted floor area. A fourth stair, combined with bleacher seating, cascades down through the central outdoor courtyard (see Figure 1).

The main mechanical/ HVAC (heating, ventilation, air-conditioning) shafts and the stacked electrical and computer technology rooms are deliberately distributed to avoid large fixed cores and maximize the capacity of the floor plates for reconfiguration.

Floor to floor heights: Generally, 14’ (4.27m), increased at ground level to 15’ (4.57m).

Most of the instructional spaces and ‘commons’ spaces are equipped with 21 inch raised floors, acting as plenums for supply air and also data and power cabling.

Primary System

Non-loadbearing interior walls and MEP (mechanical, electrical, data, plumbing) distribution

Secondary System

Tertiary System

Educational audio-visual equipment, both movable and fixed; office equipment, and mobile educational furnishings.

The project meets the equivalent of LEED certification following the guidelines of the US Green Building Council.

Sustainability

Start of the design process: 2017

Groundbreaking: 2019

Opening: August 2021

Project Schedule

John R Dale, FAIA, HED

Case Study Report

By permission of HED

Drawings

Inessa Binenbaum

Photo credits

Background

When the design team was commissioned to develop a new multi-purpose academic building for Santa Monica High School (Samohi), they were charged with designing a future-oriented facility that would provide a new direction for the redevelopment of the entire campus and respond to some key challenges facing the school District:

The Samohi Campus is over 100 years old; most of the buildings are outdated and inadequate for current needs, requiring drastic renovation or replacement;

Campus land area is at a premium – the campus houses over 2,800 students on about 26 acres (10.5ha);

Typical classrooms are undersized, crowded and rigid, and supplementary meeting spaces are inadequate;

Administrative offices are too few and too small;

Inadequate, aging athletic and physical education facilities do not meet the needs of the student population;

Inadequate parking puts pressure on limited land resources and the accessibility of facilities intended to be available to the general public;

Congested pedestrian circulation networks lengthen walking time between classes in dispersed buildings.

In spite of the challenges faced by Santa Monica-Malibu Unified School District, it is blessed with a remarkably committed and supportive community that wants a progressive and well equipped educational experience for its students. The key assets for the community are:

A diverse, highly educated and committed community, administration, staff, faculty and students;

Wide consensus around a progressive pedagogical approach now transforming education across the District;

A central, prominent site in the heart of the city;

Ongoing financial commitment on the part of the community for improving school facilities resulting from a highly effective series of local bond (fund raising) campaigns, the latest of which raised over half a billion dollars.

The campus includes some memorable landmarks: the Greek Theater (an outdoor amphitheater) and Barnum Hall – a remarkable Art Deco auditorium and stage – that frequently serve the public as well as local school events.

The concept for the new building

The realization of an open, flexible ‘loft’ building enabling continuous change is at the heart of the design concept for the Discovery Building. The exterior of the building is intended to establish a permanent sense of place and last a century or more. It is characterized by generous bands of windowsand undulating, white plaster walls that are a contemporary interpretation of the campus’ Art Deco heritage. Grand, operable glass storefronts at ground level open the building up to surrounding terraces, courtyard and adjacent plaza. The learning environment is engaging, welcoming comfortable and varied, allowing teachers and students alike to feel ‘at home’.

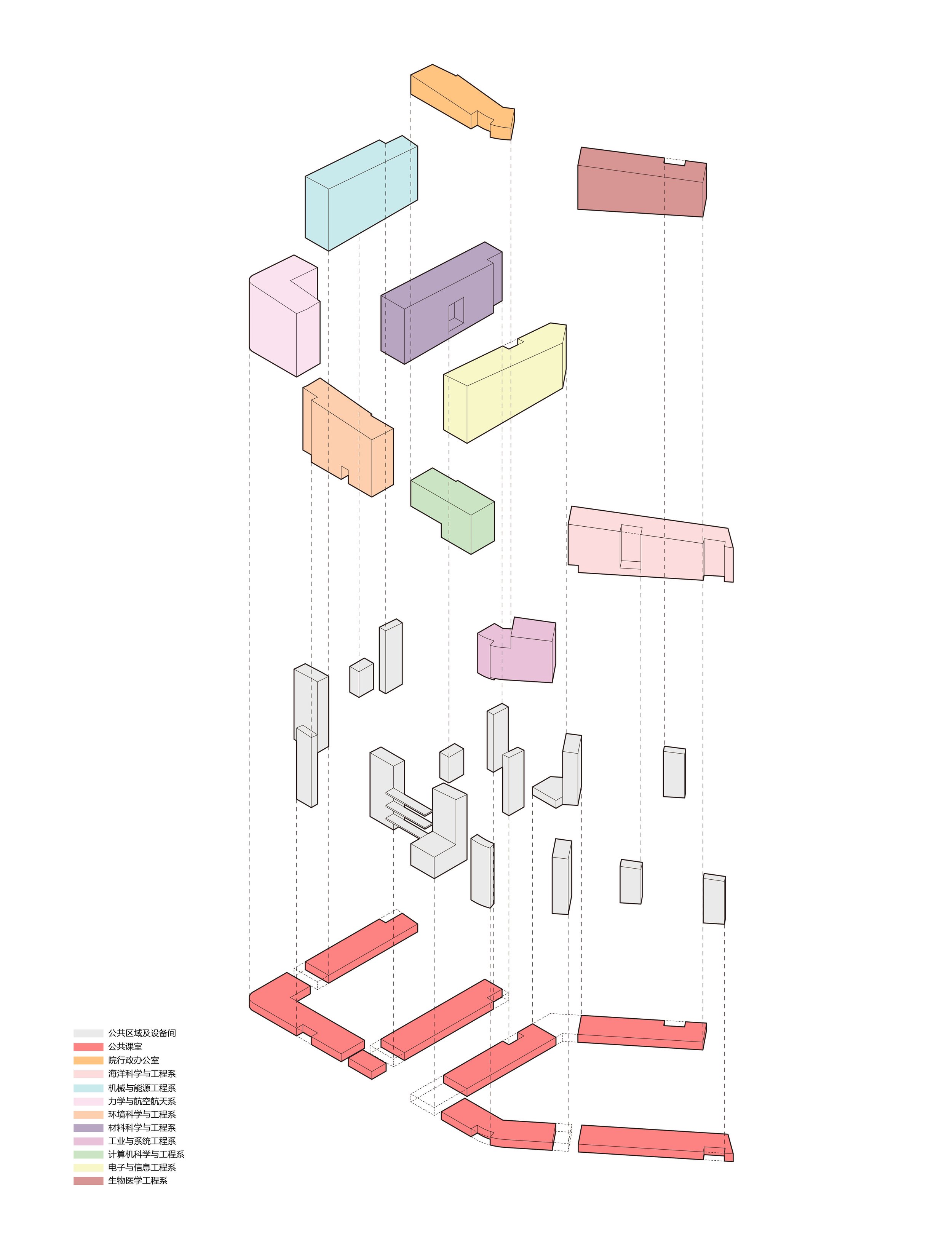

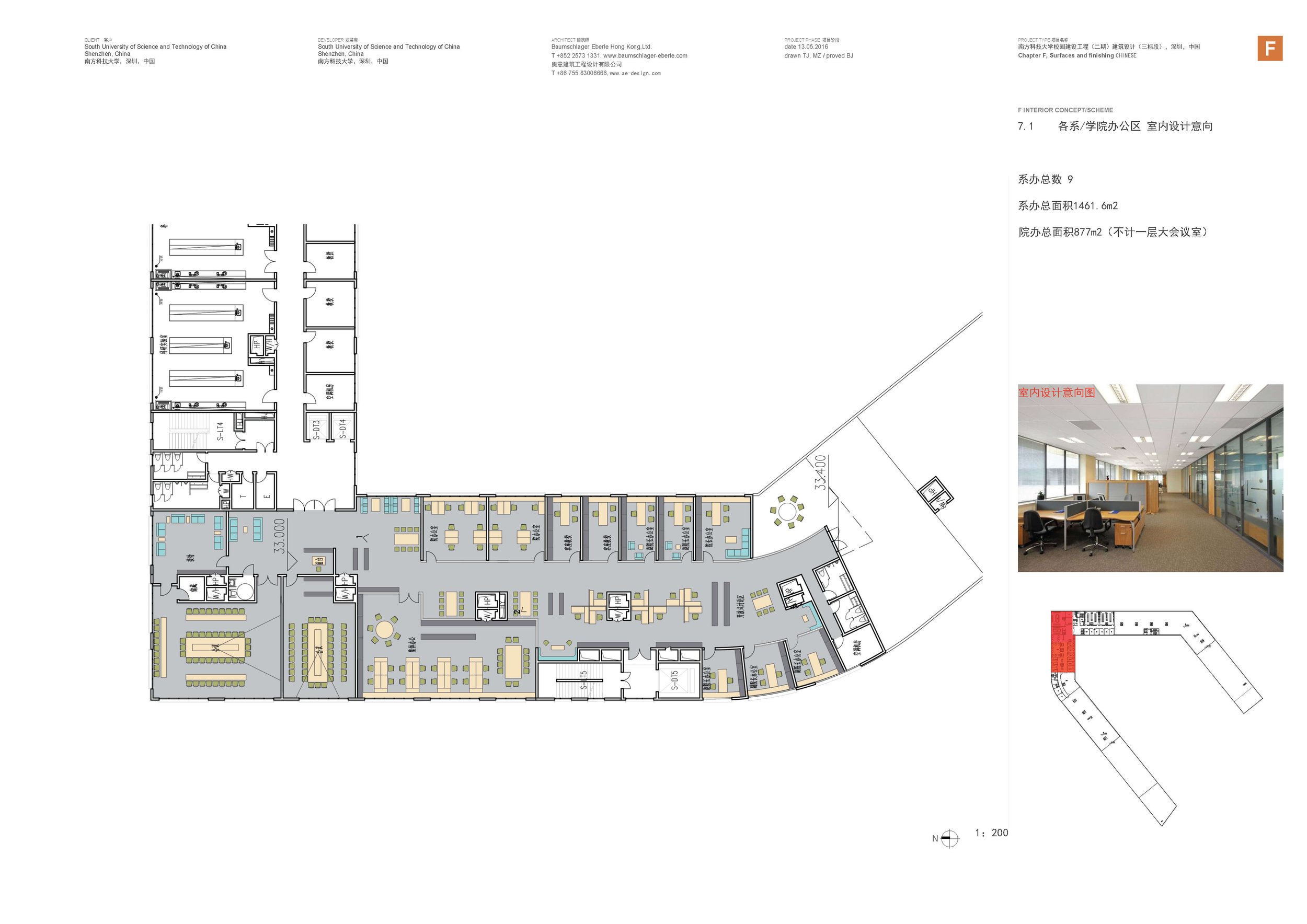

In contrast to single and double-loaded corridor layouts common in California, the six floor Discovery Building has relatively deep floor plates that allow the clustering of spaces and activities in a greater variety of sizes and formats, supporting different modes of learning. In addition to generous classroom and science laboratories, there are a variety of ‘breakout spaces’ that form a series of ‘commons’ for project-based learning, small group sessions, individual research and socializing. The program includes a computer graphics center, community meeting rooms, a medically fragile suite for longer-term students with special needs, and a large textbook distribution center. Two levels of underground parking at the base of this building have also been designed for change. With open column grids and flat slabs, these spaces can be converted to other uses in the future. Maximizing natural light and air has led to a healthy building with operable windows, trickle vents (that allow natural airflow to be filtered through a baffle system built into the window frames), folding glass walls and huge overhead doors that emphasize transparency, openness and the seamless integration of indoor and outdoor spaces, something that can be accomplished in the Southern California climate. The central courtyard, with its bleacher stairs and balconies connects the new building to the adjacent Centennial Plaza and welcomes students in.

In addition to planned learning spaces, varied, interconnected spaces, inside and out, connected by external stairs and bleacher seating, centrally located elevators and overhead bridges knit this complex together in a way that promotes chance meetings, casual socializing as well as a variety of teaching and performing opportunities. For example, the courtyard with its open stairs and bridges has already been the setting for a school choral concert; much more is being planned.

Applying open building principles

A typical school building is designed for a 50-year life cycle but is often obsolete long before it is replaced. Using Open Building principles, the design team designed an adaptable building that would accommodate frequent changes for at least 100 years, allowing teaching spaces to adapt incrementally and continuously to evolving pedagogy. By clearly distinguishing between a fixed shell and core (base building) and an infill system of non-structural partitions and by introducing a raised floor system for horizontal distribution of conditioned air supply, power and data cabling, change is more manageable financially and technically. The building will maintain its utility and adaptive capacity for years to come.

The application of Open Building strategies led to the selection of two particularly important systems:

a prefabricated steel moment frame (produced by ConXtech, Inc.)

and a raised floor system (by Tate, Inc.)

These components were chosen to achieve long term resilience and adaptability. While these are premium systems, the additional costs of using them represente less than 1 percent of the total construction cost. They have already proven to be valuable assets as changes have been made to the floor plans up until almost the conclusion of the construction phase of the project. In addition to these strategies, the modular roof-top mechanical system distributes conditioned air through a series of decentralized vertical shafts. The stair towers were pushed to the perimeter in order to maintain floor area capacity for change. At critical stages in the design of the project, the client and design team quickly came to consensus about what is essential to the future resilience of the building. The use of the steel moment frame structure means that there are no shear walls inside the building footprint (usually used in California’s strict seismic design criteria), allowing spaces to be easily reconfigured without obstruction. Data, power and floor diffusers for air distribution can be easily repositioned within spaces employing the raised floor and can respond readily to incremental change, even if it is related to the needs and teaching preferences of a single instructor.

Separation of design tasks

To be sure that the design process was not dominated by the pressure of current needs only, Discovery was designed with the separation of design tasks in mind. HED developed the shell and core (base building) approach with MRY, and then invited stakeholders to participate in design workshops to develop infill options with oversight and approval from the facilities staff. Facilities staff initiated changes during the construction phase of the project, and HED provided the documentation to achieve these changes. Teachers individually then had a direct say before completion of the project to adjust power and technology based on how they wanted to lay out their classrooms. In this case, the raised floors facilitated these changes by the contractor. Presumably in the future, the facilities staff will respond to faculty needs to adjust the floor plan. Will they document the changes in-house or seek architects to help with the changes? Probably the latter, but it will depend on the experience and expertise of the decision-makers at the time.

Resilience and sustainability

Sustainability strategies have been incorporated into this project. They ensure the building’s resilience and reduction of its carbon footprint while establishing a distinctive presence on the campus. The buildings orientation, massing and layout have, in turn, shaped these strategies to produce a holistic solution. The courtyard with its two-story living green wall combines passive strategies that allow the building to breathe and achieve natural cooling. The courtyard also brings daylighting deep into the building. At the same time, it creates a versatile social gathering space and extends the life of adjacent Centennial Plaza providing supplemental program space in the most economical way possible. The roof-top photo-voltaic arrays which offset power from the electrical grid by 34% take the form of a highly visible canopy 15 ft above the roof and provides economical shelter for the rooftop outdoor classroom. The visibility and clarity of its exposed systems becomes an important teaching tool. Similarly, the solar thermal array (which offsets 13% of heating demands of the large swimming pool that is part of the project) became a prominent cap to the living green wall and points to a more extensive array which helps to reduce the heating load of the 50-meter swimming pool below. All of the outdoor spaces are accessible to students with physical disabilities, are well-connected to adjacent indoor spaces and are readily available to all students and staff and are designed with the same palette of hardscape and plant materials.

Unanticipated Benefits

From the time it was occupied in August popularity as a new campus focal point has grown. It quickly became a home base for the northeastern corner of the campus. Its courtyard extends from Centennial Plaza to expand outdoor venues for gathering, performances and socializing. The cafeteria, placed at the intersection of two major pedestrian routes has expansive overhead doors and is open all during the day, thereby creating a seamless connection between well-populated indoor and outdoor spaces. The varied spaces defined within and outside the building to learn or just mingle informally quickly became well-used and popular with students. To quote the high school’s principal, “When they first walked into the new building, many said, ‘Wow, this is like a college campus!’” and he adds that, at the end of the day, “We have to tell them, ‘Hey, it’s time to go home!’ ”