NEXT21

A pioneering housing project in Osaka experiments with new energy systems, interior fit-outs, a facade system “kit-of-parts,” and urban greenery while using the Open Building principle of separating design tasks so that each residence can be continually designed, reconfigured, combined, or replaced independent of the others.

Next 21 (1994)

Osaka, Japan

(Structure) Yositika Utida, Shu-koh-Sha Architecture, and Urban Design Studio for Osaka Gas

The Challenge

Osaka Gas commissioned a team of architects to turn an aging housing complex into a durable and flexible residential structure that could head-off issues like aging infrastructure, environmental degradation from traditional construction, and limited community interaction in dense urban environments.

Key Issues

Rigid infrastructure meant that existing apartments could not easily adapt to changing demographics or evolving lifestyle needs.

The inefficiency of conventional construction and design practices significantly contributed to environmental degradation.

A lack of communal spaces in urban areas leads to social disconnection and decreased community cohesion.

The Ambitions

The idea was to use advanced modular design to enable residents to reconfigure apartments using standardized, interchangeable building components. At the same time, the design aimed to significantly reduce environmental impacts through innovative green technologies and to foster community engagement with thoughtfully integrated shared spaces.

Strategic Goals

A flexible framework to allow easy reconfiguration of individual living spaces. (Thirteen different architects were initially invited to design the 18 individual houses contained within the NEXT21 framework.)

Incorporate energy-efficient technologies such as solar panels, rainwater harvesting systems, advanced waste recycling facilities, and extensive greenery for improved environmental performance.

Establish communal spaces that encourage interaction and collaboration among residents.

Utilize advanced building techniques, including prefabricated modular components, standardized connectors for rapid assembly, and flexible infrastructure systems to streamline modifications and renovations.

Empower residents to have significant input into the design and layout of their apartments.

Promote biodiversity by integrating plantings and green spaces to enhance urban ecology and support wildlife.

The Realization

NEXT21’s modular design was successfully executed, featuring precisely manufactured, interchangeable building components, flexible utility systems, and innovative structural elements. These features facilitated rapid construction, easy reconfiguration, and seamless integration of sustainable technologies, meeting all strategic goals effectively.

Vital Design Choices

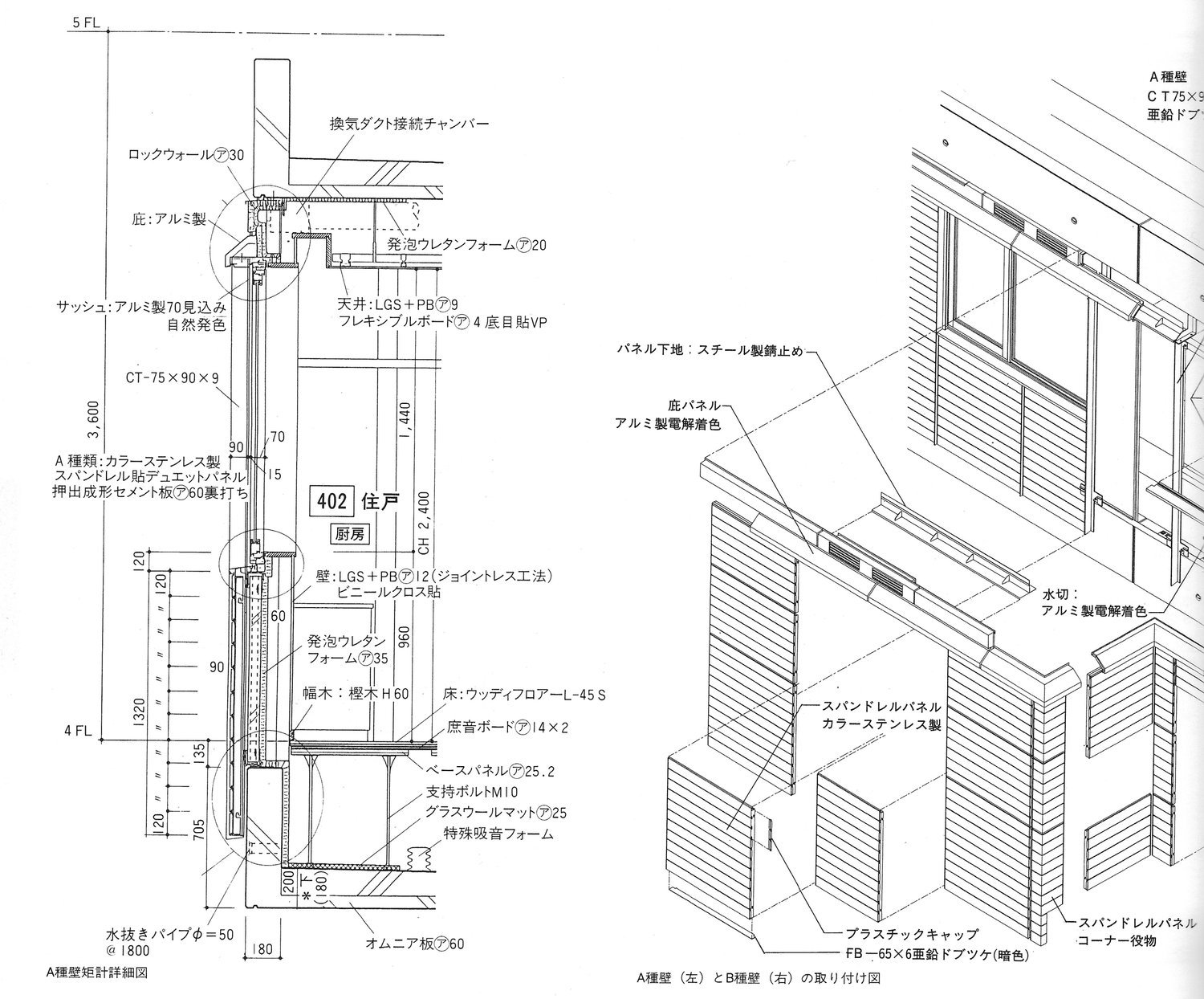

Innovative modular components like movable interior walls, interchangeable facade panels, and adjustable flooring systems to enable apartments to be easily resized and rearranged.

Each architect could design a facade reflecting the interior layout of individual dwellings with a system designed to be taken apart and installed again without need for exterior scaffolding.

The building's core framework is separated from the individual residential units’ infill, allowing for flexible interior modifications without affecting the overall structure.

Dry construction techniques for interior walls and partitions facilitate easy reconfiguration of living spaces to adapt to residents’ changing needs.

Integrated rooftop gardens and vertical greenery to enhance biodiversity, reduce heat island effects, and improve air quality within the urban environment.

A shared ecological garden to promote community interaction and provide residents with access to natural spaces.

Centralized utility shafts and double-floor systems simplify maintenance and enable efficient upgrades to plumbing and electrical systems, allowing convenient rearrangement of internal layouts.

The Results

NEXT21 has proven its enduring value through continuous adaptability and resident satisfaction, becoming a landmark for future urban housing developments worldwide.

Promising Outcomes

Many of the original dwelling units have changed with infill that adjusts changing lifestyles and needs.

NEXT21 stands as a model for adaptable urban housing, influencing subsequent residential projects and urban planning initiatives.

The building has informed local and national policies on sustainable housing and urban development.

The project has expanded our knowledge about coordinating grids and zoning for Open Building projects.

The building continues to function as a living laboratory, providing valuable data and case studies for architects, urban planners, and sustainability researchers.

NEXT21’s success is replicable, demonstrating the feasibility of implementing similar Open Building models in other urban contexts.

NEXT21 shows how Open Building can extend a structure’s lifespan—allowing interior spaces to evolve over time without major demolition—while supporting sustainability, resident agency, and urban adaptability.

-

Planning / Design

Osaka Gas and NEXT21 Planning Team (Utida, Tatsumi, Fukao, Takada, Chikazumi, Takama, Endo, Sendo)

Building Architect

Yositika Utida, Shu-koh-Sha Architecture and Urban Design Studio

Construction

Obayashi Corporation

Initial Construction

1994 (continuous ongoing renovations/transformations since)

Design System Planning

Kazuo Tatsumi, Mitsuo Takada

Dwelling Design Rules

Mitsuo Takada, Osaka Gas, KBI Architects and Design Office

Modular Coordination

Seiichi Fukao

Owner

Osaka Gas Company

Dwellings

18 (some have been combined and divided over time)

Reinforced concrete + Façade System

Support (Skeleton)

Various companies